Black History Month Feature: Pitt Honors College Student Sesi Aliu Studies the Life He Lives

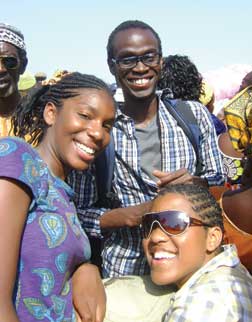

Pitt senior Sesi Aliu (center) on a ferry in The Gambia crossing the nation’s namesake river from the city of Barra to the capital of Banjul. Joining him were “hundreds of people, livestock, food, cars, and other goods.”

Pitt senior Sesi Aliu (center) on a ferry in The Gambia crossing the nation’s namesake river from the city of Barra to the capital of Banjul. Joining him were “hundreds of people, livestock, food, cars, and other goods.”Pitt senior Sesi Aliu brings the sprawling subject of Africana Studies into better focus. Abstractly, it’s the study of disparate Black cultures worldwide loosely connected by resilient traditions and a shared sense of displacement and rediscovery.

Applied to Aliu, it’s his life: born in Nigeria, moved to the United States at 8, and raised in a household equally influenced by his Yoruba extraction and Texas environs. Now 21 and an Africana Studies and French major in Pitt’s Honors College (with certificates in global and African studies), Aliu studies and explores his native West Africa as well as the places its émigrés have settled.

“My story is one thread of the larger narrative of African communities everywhere,” Aliu said.

His story began in his hometown of Lagos, a place he remembers just well enough to make him realize how much more about it he wants to learn. Flashes of his neighborhood, 1970s skyscrapers encircled by colonial architecture, and the incessant energy of Africa’s second-largest city are all he has.

In 1997, Aliu’s parents won a U.S. State Department lottery to apply for a visa and moved him and his four siblings to Austin. Against the traditional narrative of the African Diaspora, they did not flee war nor was their move involuntary. But the indelible scars of Africa’s misfortunes meant the education and comfort Aliu’s parents wanted for their children were more likely to be had in the United States, he said.

“I don’t think there’s any doubt that it was for the best,” Aliu said. “Education in Nigeria is hard to come by without the money, and, even then, the quality is questionable. Besides, there are a lot of educated Nigerians whose degrees can’t get them a job. It’s safe to say my family’s life would be a lot tougher had we stayed.”

His parents immersed the family into the local West African community—their closet friends were Nigerian, as is Aliu’s best friend. As in the majority of immigrant communities, the culture permeating his family’s home and its environs was all-encompassing. Aliu admits that his parents needed the cultural trappings of home a lot more. At 8 years old, his short life in Africa had not left him with a lot to miss. Instead, as Aliu got older, he started feeling he missed out.

“I felt there was a lot more I could know about my own culture,” he said. “For instance, I never learned Yoruba. My parents speak it, but I never needed to. I live in the United States because it was better for my family to leave Nigeria.

“My experience left me with a lot of questions about the world in general,” Aliu continued. “I thought about the legacies of colonialism, the chemistry of international relations, and differences in development and opportunities. I wondered how these issues resulted in the experience I shared with Africans around the world.”

As a Pitt student, Aliu has focused on West Africa, particularly the French-speaking nations that comprise most of the region (Nigeria is an English-speaking exception). A 2010 inductee into the Phi Beta Kappa honor society, Aliu has distinguished himself academically: He received a Humanity in Action summer fellowship in 2009, became a member of the Golden Key honor society in 2008, and was named a Helen S. Faison Scholar in 2007.

In Spring 2010, he spent a semester in Senegal that illustrated the interplay of broad similarity and cultural specificity of Africana. Again, Aliu had memory flashes of Lagos: the colonial-era buildings, the streets filled with children, and the perseverance of an ancient culture. Just like home. Except that the predominant ethnicity is Wolof, and Islam is an entrenched feature of Senegalese life. And Senegal’s capital and largest city Dakar is home to roughly one-fourth the population of Lagos.

“I had this strong overall identification with Dakar at first, but as I lived there day to day I really noticed the differences,” Aliu said. “Senegal was quite similar to Nigeria on its surface, but the underlying atmosphere was totally different.”

(During a month in the summer of 2008 and another month in the summer of 2009, Aliu lived in Malawi as part of a student-led initiative to learn about and collaborate with community-based health and social service organizations in HIV-affected areas. He was too busy each time to take in much beyond the country’s abundance of farms and rural villages, he said.)

The simultaneous feeling of kinship and contrasting cultural distinction he experienced in Senegal has encouraged Aliu to explore African culture outside of Africa. He has applied for a Fulbright Scholarship to study sub-Saharan African immigrants in France, hoping to examine the traits they share with Africans elsewhere and those developed through their experience in France.

“As an African who left my home and was raised elsewhere, I think it’s important to understand how the African experience of slavery, Diaspora, and imperialism connects and influences these similar yet distinct communities throughout the world,” Aliu said. “What I’ve learned during my life and travels has taught me that.”

Other Stories From This Issue

On the Freedom Road

Follow a group of Pitt students on the Returning to the Roots of Civil Rights bus tour, a nine-day, 2,300-mile journey crisscrossing five states.

Day 1: The Awakening

Day 2: Deep Impressions

Day 3: Music, Montgomery, and More

Day 4: Looking Back, Looking Forward

Day 5: Learning to Remember

Day 6: The Mountaintop

Day 7: Slavery and Beyond

Day 8: Lessons to Bring Home

Day 9: Final Lessons