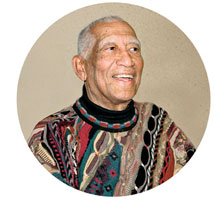

Black History Month: Ray Primas Jr.

Overcoming racism—and his own youthful anger—this University of Pittsburgh alumnus succeeded in dentistry and academia and as the leader of a public health project in Africa

In 1960, Pitt dental school alumnus Ray Primas Jr. proposed to the U.S. Department of State a plan whereby he would lead a volunteer team of American doctors to newly independent African countries to treat underserved communities there.

In 1960, Pitt dental school alumnus Ray Primas Jr. proposed to the U.S. Department of State a plan whereby he would lead a volunteer team of American doctors to newly independent African countries to treat underserved communities there.

But State Department officials rejected the idea, arguing that Africans preferred aid programs run by White Americans because Blacks did not have enough pull in the United States to get things done. Primas laughed at the absurdity of that response.

“That’s what they believed, and they were wrong,” Primas says. “They felt African Americans could not relate to Africans, and vice versa.”

Among the power elite in Washington, D.C., in those days, “the perception of Africa was crazy,” recalls Primas. “The perception of Black America was crazy. They [government officials] gave me all kinds of reasons why my health project wouldn’t work.”

Rather than take “No” for an answer, however, Primas described his project in a letter to newly inaugurated President John F. Kennedy, who liked the idea and instructed the State Department to support it.

Soon, Primas and a Detroit physician were pitching the plan in three African countries.

“The same people [in the State Department] who said they couldn’t do it chartered flights, hired cars, and gave me everything I needed,” Primas says, laughing.

Ultimately, though, the project never got off the ground. “Northern Nigeria agreed to do it, but as soon as we got back to the United States, the State Department said it was not ready to do its part,” Primas explains. “But they said they would consider me an expert on Africa and call on me at another time.”

At 81, Primas tends to laugh as he tells stories of the racism he faced in his professional and personal lives.

One reason is that race bigotry failed miserably to hold him back. In the 60 years since he graduated from Pitt, Primas has taught at all education levels—including lecturing as a tenured professor in the University’s Graduate School of Public Health (GSPH)—and he ran two successful dental practices. While his initial proposal for a volunteer program to Africa never came to fruition, Primas launched in the 1970s a GSPH-based health education project in three African countries.

“I’ve had some fabulous experiences,” Primas says. “I made a lot of friends and influenced a lot of people. I can brush that other stuff off. I feel sorry for those who missed the opportunity to have a close relationship with me just because of skin color.”

Primas wasn’t always so coolly philosophical. As an 18-year-old first-year student at Pitt in 1943, he responded angrily to the racism he regularly encountered at the University and in Pittsburgh generally.

Dentistry was not at the top of Primas’ career list, but everyone he knew had urged him to follow in the footsteps of his father, prominent North Side dentist

H. Raymond Primas Sr., who graduated from Pitt’s dental school in 1924 and later taught classes here. The elder Primas was revered for his devotion to the multiracial community of Manchester, where the Primas family resided. He treated children at the North Side’s Home for Colored Children—since renamed Three Rivers Youth (TRY)—from 1930 until 1956, the year he died, and served as the home’s treasurer and on its board of directors. (Pitt celebrated TRY’s 125th anniversary in 2006.) During the Depression, Ray Primas Sr. let patients pay for dental work with food or by doing painting or roofing work.

In addition to enabling him to emulate his father, attending Pitt’s dental school seemed more attractive to young Raymond than military life.

“The draft board was breathing down my neck” in 1943, he remembers. “My dad had a good reputation, and that [emulating one’s father] was what one tended to do. At the time, there were very few opportunities for us of the minority races. I could hardly do anything else” than study dental medicine.

His father’s reputation smoothed Primas’ professional path somewhat, he says. But still, a dark complexion brought with it limited opportunities and daily indignities. For all the respect Raymond Primas Sr. had earned, for example, he still was expected to ride the freight elevator, not the passenger elevator, to some professional meetings of the local dental society, his son recalls.

In his Pitt dental school class, Raymond Jr. represented half of the African American enrollment. The other Black student was Michigan native George A. Millben, who, like Primas, would graduate from Pitt’s dental school in 1947. (Primas also earned his B.S. degree at Pitt in 1946.)

“They decided to bring us in two-by-two to keep each other company. That’s the way it was. It was a pretty bad environment” for Blacks at Pitt back then, says Primas. (As late as 1957, he adds, he was still suffering what he believes were racially motivated slights here. “Ten years after graduation, for example, I was accepted by Dr. Leonard Monheim in his anesthesiology course,” Primas says. “But when the medical school dean found out I was taking the course, the dean made my acceptance ‘provisional.’ What did that mean? That’s a good question. The guy who did it is dead.”)

Primas’ grades in dental school did not match his honors-laden high school record. His father and Millben, his Black classmate, who was 10 years older than Raymond Jr., advised him to keep his anger in check.

“I had to temper my responses because I wanted to accomplish my goals,” Primas says. “Millben kept me together. He said, ‘Cool it. Just get your degree and get out of here.’ And I did.”

After graduating, Primas applied for an oral surgery residency in Pittsburgh, but found such opportunities nearly nonexistent here for African Americans. He was referred to Harlem Hospital, far away from his family and neighborhood.

Primas never landed a residency; he instead opened a private practice in Aliquippa so he could operate in a local hospital. He later joined his father’s practice and worked alongside him until Raymond Sr.’s death. By the early 1960s, Primas had extended the practice and ultimately oversaw five other dentists, four of them women.

To Primas’ surprise, the State Department contacted him in 1962 to help with a problem in the African nation of Dahomey, now called Benin. Two mobile health units donated by the United States to that country were sitting on the health minister’s lawn, with no gas and with loads of medical equipment that wasn’t serving anyone.

“One had a big sign on it that said ‘A Gift From the United States to the People of Dahomey,’ and it was just sitting there on the lawn, out of gas,” says Primas. “The American ambassador stated in a cable that it embarrassed him. That’s how the State Department presented it to me: ‘We have an embarrassing situation. Can you help us?’”

Primas traveled to Dahomey, inventoried the medical equipment, and toured the country, making connections with physicians and government officials. The State Department ultimately entrusted the mobile health units to the New York-based exchange program Operation Crossroads Africa. But Primas’ effectiveness in straightening out the “embarrassing situation” had impressed department officials.

During a trip to Washington in 1970, a representative of the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID)—a State Department agency—asked Primas, by then a professor in GSPH, whether Pitt would be interested in running a health-education project in the African nations of Cameroon, Central African Republic, and Chad. USAID would fund the project through a for-bid contract. The university that won the contract would work with the Organization for the Control of Endemic Disease in Central Africa (OCEAC), an organization of French military doctors operating in Francophone Africa.

Primas was told that to get the contract, he needed to demonstrate “total university support.” He proposed the idea to then-Chancellor Wesley W. Posvar, who was looking for ways to recruit and enroll more African Americans at Pitt. Primas won Posvar’s support, Pitt bid for the project, and GSPH received a five-year, $1.25 million contract in 1970. The money funded six technicians to work in three African countries with Primas overseeing the operation from GSPH, where he had earned a master’s degree the year before.

By the time the contract had expired in 1975, what Primas calls a “heart event” had convinced him, at age 50, to move to sunny, dry Scottsdale, Ariz. A few years later, he sold his Pittsburgh practice and started another in Scottsdale. He worked at the county hospital there for three years and provided dental service to the county’s homeless before retiring in 1992.

Ironically, Primas found less racism in lily-white Scottsdale than he had in Pittsburgh, he says. “When we’d see a person of color in Scottsdale, we’d cheer. That’s how few of us there were,” Primas says, laughing. “Racism wasn’t nonexistent, but it wasn’t as pervasive.”

Before he had left Pittsburgh, Primas says, Pitt had offered him a job helping to recruit Black students—but no one would tell him what his budget would be, he complains. He sensed he was being offered a token position.

“I’ve had a very tumultuous relationship with the University of Pittsburgh. Pitt was my school, but I carried a grudge against the University for a long time,” says Primas—partly, he points out, because he cared too much about his alma mater to overlook its faults the way he had learned to laugh off racism elsewhere.

But Primas finally let go of his resentment upon moving back to Pittsburgh last year and discovering what he sees as a new concern and respect for African Americans at Pitt under the leadership of Chancellor Mark A. Nordenberg.

“In many respects, it’s almost hard for me to believe the openness of Pitt today toward Blacks,” says Primas. “The chancellor has done an excellent job. I’m proud of this University.”

Other Stories From This Issue

On the Freedom Road

Follow a group of Pitt students on the Returning to the Roots of Civil Rights bus tour, a nine-day, 2,300-mile journey crisscrossing five states.

Day 1: The Awakening

Day 2: Deep Impressions

Day 3: Music, Montgomery, and More

Day 4: Looking Back, Looking Forward

Day 5: Learning to Remember

Day 6: The Mountaintop

Day 7: Slavery and Beyond

Day 8: Lessons to Bring Home

Day 9: Final Lessons