Chancellor's Report: Pitt Striving to Attain Ever-Higher Levels of Educational Strength…and Beauty

This is the print version of the report delivered by Chancellor Mark A. Nordenberg at the June 25, 2010, annual meeting of the University of Pittsburgh Board of Trustees.

The Impact of Education

Mark A. Nordenberg

Mark A. NordenbergWhen we think about the value of higher education, many of us tend to focus first on its impact in individual lives. After all, acquiring a high-quality higher education has long been viewed as an essential step in the successful pursuit of the American dream. And it certainly appears that all of us are among its grateful beneficiaries.

But there also is the impact of higher education as an essential force in the advancement of our collective interests. That broader dimension of education’s power was described by Hugh Henry Brackenridge, our founder, some 225 years ago. In arguing for the creation of the log-cabin academy that later would become our University, he stated simply, “We well know the strength of a state greatly consists in the superior mental powers of its inhabitants.”

That statement was made by Mr. Brackenridge when Pittsburgh still was a frontier outpost. Certainly, the place of education has become even more critical to our shared progress as we have marched through time to a highly connected world and to a knowledge-based economy. And even as concerns have grown about the quality of the basic education being delivered in many of this country’s primary, middle school, and high school classrooms, America’s best-known providers of higher education—mainly its research universities—have continued to occupy a position of great international respect.

Some 13 years ago, not long after many of us began working together, Henry Rosovsky, the former dean of Arts and Sciences at Harvard, wrote:

[F]ully two-thirds to three-quarters of the best universities in the world are located in the United States. . . . What sector of our economy and society can make a similar statement? One can think of baseball, football, and basketball teams, but that pretty much exhausts the list. . . . It has been suggested to me that we are home to a similar proportion of the world’s leading hospitals. Since most of these are part of university medical schools, my point is only reinforced.

Reduced Support and Growing Needs

Despite their well-earned stature, these high-performing centers of higher learning—which Dean Rosovsky labeled “a special national asset”—in recent years have faced new sets of pressures, most of them economic. As financial support for their work has eroded, not just during the current recession but over a more extended period, even elite universities have sometimes seemed vulnerable. And the pressures have been most intense on the public side.

I already have discussed, perhaps too often to suit you, the challenges that recently have come Pitt’s way, and I will not return to them now. But to provide some sense of national flavor, let me cite two examples from this month’s news:

• The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, one of the country’s truly fine public research universities, reported that it had lost 53 of 77 professors who were recruited by other universities during the past academic year and expressed some doubt that it would be able to move into a new $92 million high-tech teaching and research building because it did not have the money to operate the facility; and

• Rutgers, our AAU and Big East neighbor in New Jersey, just cancelled scheduled pay increases and froze salaries to deal with what it called an “extreme financial crisis.”

Even as such budgetary pressures continue to mount, Georgetown’s Center on Education and the Work Force last week issued a report entitled “Help Wanted: Projecting Jobs and Education Requirements Through 2018.” The release accompanying the report summarized its general finding—that “millions of workers [are] at risk of being left behind” as the “shift to [a] ‘college economy’ intensifies.”

More specifically, the report predicts that “by 2018, 63 percent of all jobs will require at least some post-secondary education.” This compares with 59 percent of all jobs today and just 28 percent in 1973. Moving from percentages to absolute numbers, the report predicts that “we will need 22 million new college degrees” by 2018 “but will fall short of that number by at least 3 million . . .”

This shortfall, according to the report, “is the latest indication of how crucial post-secondary education and training have become to the American economy. The shortfall—which amounts to a deficit of 300,000 college graduates every year between 2008 and 2018—results from the burgeoning demand by employers for workers with high levels of education and training.”

“The impending shortage,” the report’s authors continue, “lends urgency to the question about the financing of America’s college and university system.” And “failing to achieve the mix of funding and reform required . . . will not only leave more and more Americans behind—it will damage the nation’s economic future. And that, quite simply, is something we cannot afford.”

Earlier in the year, President Obama had responded to these same troubling trends by declaring, to a joint session of Congress, that by 2020, “America will once again have the highest proportion of college graduates in the world.” Programs to increase college completion rates have been launched since then, and Pitt is a part of them. Hopefully, the national product of those programs will be the elevation of student performance and not a relaxation of standards.

Students and Alumni of Impact

Anyone who attended our May commencement ceremony at the Petersen Events Center—or any of the related ceremonies held on our regional campuses or sponsored by specific schools—would have left with the sense that Pitt was doing its share. “The Pete” was packed with happy graduates and proud family members and friends. They were treated to a masterful keynote address, focusing on “grand challenges,” which was delivered by our friend and Board of Trustees colleague John Swanson; to well-deserved recognition of our distinguished Provost, Jim Maher; and to memorable remarks from Lance Bonner, representing the graduating class, and Jim McCarl, representing the alumni. And in terms of both student attainment and alumni impact, Pitt continues to move through a very special period.

When we met in February, we celebrated, with good reason, the selection of Eleanor Ott as a 2010 Rhodes Scholar—Pitt’s third Rhodes Scholar in the past five years. Since only 32 Rhodes Scholars are selected every year from among the very best students at the country’s top colleges and universities, that is quite a record. And it is a record to which we have added significantly since our late February meeting. Let me give some examples:

• Nicholas DeStefino, an Honors College junior majoring in neuroscience and history in our School of Arts and Sciences, was named a 2010 Goldwater Scholar—the highest national honor for an undergraduate in the sciences, mathematics, or engineering. Pitt has claimed 35 Goldwater Scholarships since 1995;

• Amy Scarbrough, an Honors College junior studying ecology, evolution, and bioinformatics in our School of Arts and Sciences, was named a 2010 Udall Scholar—the highest national honor for undergraduates committed to careers related to the environment. Only 80 Udall Scholars were named nationally;

• Weilu Tan, an Honors College senior who majored in political science and Japanese and was a member of this May’s graduating class, was the first Pitt student and one of just eight students nationally to receive a Carnegie Endowment for International Peace Junior Fellowship, which will support work that she will do, under the guidance of a Carnegie Endowment senior associate, focused on U.S.-China relations;

• Three Honors College juniors—Jonas Caballero, Katie Manbachi, and Stephen Petrany—were selected to receive Humanity in Action summer fellowships. Our dear friend Alec Stewart referred to these awards as coming from “the foremost collegiate program for desirably integrating the production of thinkers and leaders,” and this is the fifth year in a row that Pitt students have successfully competed for them;

• Michael Freedman and Matthew Perich, Honors College seniors who earned their degrees in the School of Engineering, received awards from the Whitaker International Fellows and Scholars Program, which is designed to provide international experience and insight in the field of biomedical engineering. This is just the fifth year of the Whitaker competition and the first year that Pitt students applied. Only 23 graduate-level fellowships were awarded, with two of them claimed by these very recent Pitt graduates;

• Four Honors College students have received 2010 Boren Scholarships for International Study. These awards are funded by the National Security Education Program and focus on geographic areas, languages, and fields of study deemed critical to U.S. national security. A total of 138 awards were made nationally, and four of them came to Pitt. Our 2010 Boren Scholars and their destination countries are Utsav Bansal (China), Heather Duschl (Japan), Michelle Sattazahn (China), and Gregory Withers (Tajikistan);

• Six recent Pitt graduates (Joshua Cannon, Erin Donnelly, Erin Rodriguez, Stanley Steers, Michaelangelo Tabone, and Allyson Tessin) and seven Pitt graduate students (Emma Baillargeon, Julia Bursten, Erin Crowder, Eric Griffin, Katherine Martin, Aarthi Padmanabhan, and Lynn Anne Worobey) were awarded National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowships. This is the oldest graduate fellowship program of its kind and is designed to support outstanding students pursuing research-based degrees in science, technology, engineering, and math;

• Two School of Arts and Sciences graduate students—Boryana Dobreva from the German department and Jonathon Livengood from the Department of History and Philosophy of Science—received dissertation completion fellowships through a competition sponsored by the American Council of Learned Societies and the Andrew Mellon Foundation. Only 65 awards were made nationally, and two came to Pitt; and

• Pitt doctoral student Kakenya Ntaiya, who is working on her dissertation in our School of Education, was one of just 14 “visionary young trailblazers” to be named a 2010 National Geographic Emerging Explorer for her dedication to bettering the lives of young girls in her small village in Kenya.

That last example provides a natural bridge to the amazing record of alumni achievement compiled by former Pitt students during the recent past. I say that, of course, because Wangari Maathai was a Pitt graduate student from Kenya who returned home and did the work that resulted in her selection for the Nobel Peace Prize. Who knows, then, what wonderful work Kakenya Ntaiya might do with her Pitt degree?

And in terms of wonderful work, it really is astounding that during the last decade, Pitt graduates claimed not only the Nobel Peace Prize but also the Nobel Prize in Medicine, the National Medal of Science, the Fritz Medal in Engineering, the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction, the Shaw Prize in Life Science and Medicine, and the Albany Medical Center Prize in Medicine, among many other national and international awards. I doubt that many other universities can compare with that outstanding record.

And prospects for the future look very bright, because beyond specific examples of current student achievement, we also know that we continue to attract, retain, and graduate students at record-setting rates. Just looking for a moment at current figures relating to this coming fall’s freshman class on this campus:

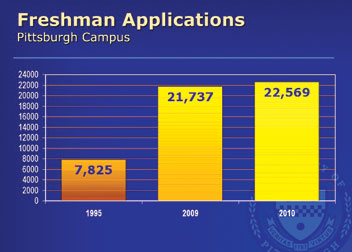

• We know that it will be drawn from the largest applicant pool in our history. Applications—just for the undergraduate programs on this campus—stand at 22,569, compared to 21,737 last year and 7,825 in 1995;

• We know that it will be drawn from the largest applicant pool in our history. Applications—just for the undergraduate programs on this campus—stand at 22,569, compared to 21,737 last year and 7,825 in 1995;

• And while these numbers may change some between now and the end of August, admit-paid applicants have an average SAT score of 1274, compared to 1264 last year and 1110 in 1995; and

• Similarly, the percentage of admit-paid applicants who ranked in the top 10 percent of their high school graduating classes stands at 51 percent, compared to 49 percent last year and 19 percent in 1995.

A Committed and Accomplished Faculty

These high-potential students are nurtured in their growth by outstanding teachers and advisors. During the final weeks of the spring term, we extended special recognition to this year’s winners of the Ampco-Pittsburgh Prize for Excellence in Advising (created by our good friend and fellow trustee Bob Paul), the David and Tina Bellet Teaching Awards in the School of Arts and Sciences, the Provost’s Awards for Exceptional Mentoring of Doctoral Students, and the Chancellor’s Distinguished Teaching Awards.

Of course, Pitt faculty members are not only expected to share existing knowledge through their teaching, but also to generate new knowledge through their research and scholarly work. And we are among the nation’s leaders in building bridges between our current students, including undergraduates, and the pioneering research work being done by members of our faculty.

One telling, and very recent, example is the recognition and support won by Eberly Family Professor and Department of Biological Sciences Chair Graham Hatfull and his colleagues. Professor Hatfull, who is a distinguished researcher with a true passion for involving students in such work, won renewal as one of just 13 Howard Hughes Medical Institute Professors nationwide—a group described by the Institute as “leading research scientists who are committed to making science more engaging to undergraduates.”

Professor Hatfull’s department also received a $1.2 million Howard Hughes Precollege and Undergraduate Science Education grant, which will support its summer undergraduate research programs. Pitt was one of only seven universities nationally—along with Harvard, Louisiana State, MIT, UCLA, Washington University in St. Louis, and Yale—to receive both a Howard Hughes professor award and an undergraduate science education grant this year.

Of course, the strength and richness of our research program is reflected in many ways:

• We see it in the honors that are regularly claimed by members of our faculty and that I regularly chronicle in these meetings and in other reports;

• We see it in programs, tied to our own scholarly strengths, that enrich campus life, provide meaningful connections to the broader community, and attract leading scholars from other institutions. The Race in America conference, sponsored by the Center on Race and Social Issues in our School of Social Work, is one very recent example; and

• We see it when a leader as prominent as Admiral Mike Mullen, the chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, chooses to spend a day in Pittsburgh, with most of his time here focused on research projects with the potential to improve the lives of America’s wounded warriors.

Of course, the strength of our research program also is quantitatively reflected in the amazing growth in our portfolio of grants. Last year, our research expenditures totaled $654 million dollars, an all-time high. This year, when the books are closed, we expect that number to approach, or maybe even exceed, $730 million. That dramatic single-year increase, which could approach 12 percent, is, to be sure, fueled by federal stimulus funding. But it also is an unmistakable sign of our faculty’s ability to successfully compete, on the basis of merit, with researchers from the best universities in the country for whatever pools of research dollars are available.

As we have discussed in the past, those research expenditures support pioneering projects, generate local jobs, and are an accepted measure of institutional strength. Earlier this week, the Pittsburgh Business Times released its annual list of Pittsburgh’s largest employers. Here were its top four for the Pittsburgh metropolitan area: UPMC (36,755 jobs), the federal government (18,738 jobs), state government (13,805 jobs), and the University of Pittsburgh (11,328 jobs).

UPMC’s numbers, standing alone, are stunning. And it also is worth noting that if you back out federal and state government—and many lists do look only at nongovernmental employment—then UPMC and Pitt become first and second. That, of course, underscores messages that now regularly are delivered about the importance of the “eds and meds” to this region’s economy.

It also is worth noting that these are only the numbers of actual employees on payroll, with no consideration given to any multiplier effects. But returning to research for a moment, by frequently used conventions, 36 jobs are generated by every $1 million in research and development expenditures. Our anticipated research expenditures for this year then, taken alone, will have supported, directly and indirectly, more than 26,000 local jobs.

Elevating Our Stature

As stated, those research numbers also are one clear measure of institutional stature. Going into the year, we ranked fifth nationally in terms of the funding attracted by our faculty from the National Institutes of Health—trailing only Harvard, Johns Hopkins, Penn, and the University of California at San Francisco. We also ranked in the top 10 nationally in total federal science and engineering research and development support. These are rankings that matter.

As stated, those research numbers also are one clear measure of institutional stature. Going into the year, we ranked fifth nationally in terms of the funding attracted by our faculty from the National Institutes of Health—trailing only Harvard, Johns Hopkins, Penn, and the University of California at San Francisco. We also ranked in the top 10 nationally in total federal science and engineering research and development support. These are rankings that matter.

And in the last few weeks, we received another ranking that we have been tracking carefully for the last decade—earning a place, for the fourth consecutive year, in the very top cluster of public research universities in the objective assessment annually published by The Center for Measuring University Performance. Also included in that distinguished group were Berkeley, Illinois, Michigan, North Carolina, UCLA, and Wisconsin.

In the inaugural edition of The Top American Research Universities report, which was released in 2000, its authors stated: “Research universities live in a highly competitive marketplace, and none of those in the top categories is likely to cease improving. This means that to get relatively better, a university must match and then exceed the growth of its competitors. This is a major challenge.”

That basic message was underscored by the authors in their just-released 2009 report, where they note the “remarkable stability” in the rankings of research institutions, particularly “at the top of the distribution.” But to rise from the study’s fourth cluster to its first cluster, as we have done, Pitt improved its relative position with respect to 15 of America’s strongest research universities—Arizona, Florida, Georgia Tech, Iowa, Minnesota, Ohio State, Penn State, Purdue, Texas, Texas A&M, UC-Davis, UC-San Diego, UCSF, Virginia, and Washington. That was no small feat.

The Beauty of the University

To maximize their impact, universities clearly must be institutions of strength. In many different ways, universities also are places of real beauty. In fact, John Masefield, the late Poet Laureate of England, once said:

“There are few earthly things more beautiful than a university. It is a place where those who hate ignorance may strive to know, where those who perceive truth may strive to make others see. Where seekers and learners alike, banded together in the search for knowledge, will honor thought in all of its finer ways, will welcome thinkers in distress or exile, will uphold ever the dignity of thought and learning, and will exact standards in these things.”

Here at Pitt, we know about the physical beauty of a university. In fact, we have worked hard to preserve, restore, and add to the beauty of our University, even as we have enjoyed it.

At Pitt, we also know about the deeper beauty, to which Masefield refers, that is tied to our noble mission. We are moved by that beauty on a daily basis as we work with and support those whose committed efforts to develop human potential, to expand human knowledge, and to contribute to the greater good define and give value to our University.

At Pitt, we have been privileged to see the beauty that exists, to use Masefield’s phrase, in the pursuit of noble goals by means that meet “exacting standards.” Those are the kind of standards that we set for ourselves and that have driven our progress as we have worked, in our own words, “to clearly and consistently demonstrate that this is one of the finest and most productive universities in the world.”

And at Pitt, we also know that there is a special beauty in the human bonds that come from working together to meet and defeat challenges, to seize and create opportunities, and to build strength in an institution that contributes so much to so many.

In so many different ways, then, our University is a thing of beauty. And, because of you and all that you—and so many others—have done for Pitt, this is a more beautiful place this year than it was last year or the year before that. Everyone who is, or will be, touched by Pitt, then, is in your debt and, for them, I thank you . . . even as I also issue the unnecessary reminder that there are even higher levels of both strength and beauty to attain, which means that there still is a lot more work to be done.

Other Stories From This Issue

On the Freedom Road

Follow a group of Pitt students on the Returning to the Roots of Civil Rights bus tour, a nine-day, 2,300-mile journey crisscrossing five states.

Day 1: The Awakening

Day 2: Deep Impressions

Day 3: Music, Montgomery, and More

Day 4: Looking Back, Looking Forward

Day 5: Learning to Remember

Day 6: The Mountaintop

Day 7: Slavery and Beyond

Day 8: Lessons to Bring Home

Day 9: Final Lessons