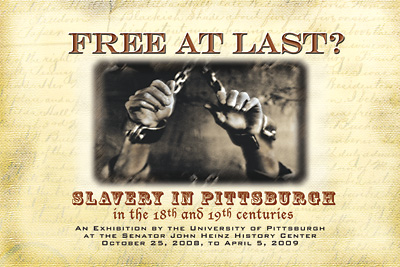

Free at Last? Exhibition on Slavery Opens Oct. 25

Pitt’s show at Heinz History Center illuminates slavery among Pittsburgh’s early settlers, rewrites region’s past.

A pathbreaking exhibition, Free at Last? Slavery in Pittsburgh in the 18th and 19th Centuries, writes a new chapter in the early history of race relations in this region. It explores in depth for the first time the little-known fact that slavery persisted in Western Pennsylvania through the years directly preceding the Civil War.

Free at Last? was created by the University of Pittsburgh in partnership with the Senator John Heinz History Center in observance of the 250th anniversary of the founding of Pittsburgh and the 200th anniversary of the abolition of the Atlantic slave trade in the United States. It centers on 55 handwritten records discovered last year and dating from 1792 to 1857 that document this area’s decades-long involvement with Black slavery and indentured servitude.

The exhibition will be on display from Oct. 25, 2008, through April 5, 2009, in the McGuinn Gallery of the Senator John Heinz History Center, 1212 Smallman St., Strip District. A by-invitation opening reception will take place on Friday, Oct. 24.

The original slavery-related documents were discovered in 2007 by staff in the Allegheny County Recorder of Deeds Office. They were later transferred to the Heinz History Center by then-Recorder of Deeds Valerie McDonald Roberts, a graduate of Pitt’s School of Arts and Sciences and School of Health and Rehabilitation Sciences. The discovery by Roberts, now manager of the County Department of Real Estate, spurred Pitt Vice Chancellor for Public Affairs Robert Hill to investigate further.

“These and other slavery-related records shouted out from their aged pages the need to be publicly inspected,” said Hill, executive-in-charge of the exhibition. “They suggested to me that the much bigger story must be told of how and why slavery came to Western Pennsylvania, the locus of the 55 records and the focus of the exhibition. And equally important were the means by which slavery in this region was legally ended and the extent to which slavery and the effects of slavery persisted.”

Subsequent research led to finding:

- a copy of the Westmoreland County Slave Registry, 1780-1782 (During those years, Pittsburgh was part of Westmoreland County, and would continue to be so until 1787);

- a copy of the Registry of the Children of Slaves in Allegheny County, 1789-1813; and

- census data that report some of this region’s most prominent 18th- and 19th-century citizens included slaveholders and nonslaveholders alike.

The 55 papers showcased in the exhibition include a bill of sale between two Blacks in which a husband purchased his wife in order to free her, a record of 36 Blacks who were transported to Pittsburgh and to freedom from Louisiana, a paper concerning a free Black who was wrongly imprisoned as a fugitive slave, and a 22-year indentureship involving a 6-year-old child.

The exhibition begins by taking visitors through a simulated slave ship and showing the terror and powerlessness experienced by African slaves during their Middle Passage from Africa to America. It traces the region’s history from the establishment of Fort Pitt in 1750 through 1780—when Pennsylvania became the first state to enact a law for the gradual abolition of slavery, replacing it with a form of term slavery known as indentured servitude—to the decades leading up to the Civil War. Throughout most of this period, there was a constant fear of recapture felt by fugitive slaves and the unending insecurity felt by free Blacks, who were still vulnerable to being kidnapped and sold into slavery.

Free at Last? contains lifelike wax figures of fugitive slaves as well as the gripping tales of their successful escapes to freedom.

Among the stories are those of:

- Henry Highland Garnet, who, on the pretext of attending a funeral, traveled to Pennsylvania by wagon and foot with his family of 10. He became president of Pittsburgh’s Avery College and founded the city’s first Black Presbyterian church, the 140-year-old Grace Memorial; and

- Ellen and William Craft, a married couple, who executed a successful plan to disguise the light-complexioned mulatto Ellen as a sickly white gentleman accompanied by “his” manservant (William). Years later, their great-granddaughter, also named Ellen Craft, lived in Pittsburgh and married Pitt Arts and Sciences alumnus Donald Dammond, the nephew of 1893 Pitt School of Engineering alumnus William Hunter Dammond, the first Black graduate of the University of Pittsburgh.

- The exhibition also includes biographies of prominent slaveholding and nonslaveholding Pittsburghers, descriptions of leading Black and White abolitionists, never-before-exhibited vintage artifacts from The John L. Ford Collection, and the earliest-known visual representation of the city and its dwellings—a George Beck painting from the holdings of the Pitt Library System that dates back to the first decade of the 19th century.

- Pitt offers its own expertise on the subject of slavery in this region with three esteemed Pitt faculty members’ books on display within the exhibition: The WPA History of the Negro in Pittsburgh (University of Pittsburgh Press, 2004), edited by history professor Laurence A. Glasco, historical director of the exhibition and winner of the 2008 Pitt African American Alumni Council Sankofa Award; The Slave Ship: A Human History (Viking, 2007) by history professor Marcus Rediker, chair of the department and recipient of the $50,000 George Washington Prize in 2008; and From Slavery to Freedom (New York University Press, 1999) by Seymour Drescher, University Professor of History and Sociology and winner of the 2003 Frederick Douglass Book Prize.

- Pitt’s Office of Public Affairs created the exhibition with support from the Office of the Chancellor and in partnership with the Senator John Heinz History Center. The Heinz History Center, the largest history museum in Pennsylvania, is an affiliate of the Smithsonian Institution.

See the highlights at here.

Other Stories From This Issue

On the Freedom Road

Follow a group of Pitt students on the Returning to the Roots of Civil Rights bus tour, a nine-day, 2,300-mile journey crisscrossing five states.

Day 1: The Awakening

Day 2: Deep Impressions

Day 3: Music, Montgomery, and More

Day 4: Looking Back, Looking Forward

Day 5: Learning to Remember

Day 6: The Mountaintop

Day 7: Slavery and Beyond

Day 8: Lessons to Bring Home

Day 9: Final Lessons