From Log House Academy to Leader in Education, Pioneer In Research, and Partner in Regional Development

The University of Pittsburgh: 225 Years of Building Better Lives

The Formative Years

Hugh Henry Brackenridge

Hugh Henry BrackenridgeTwo hundred twenty-five years ago, in 1787, delegates meeting at Philadelphia’s State House replaced the agreement creating a loose confederation of sovereign states with an enduring blueprint for democracy—the Constitution of the United States. That same year, educator, attorney, author, and distinguished member of Pennsylvania’s General Assembly Hugh Henry Brackenridge successfully urged his legislative colleagues to establish a seat of higher learning in Pittsburgh. His passionate pleas—“Academies are the furnaces which melt the natural ore to real metal; the shops where the thunder-bolts of the orator are forged”—engendered “An Act for the Establishment of an Academy or Public School in the Town of Pittsburgh” on Feb. 28, 1787.

The preamble to the act declared the legislature’s intent:

The education of youth ought to be a primary object with every government … Be it enacted … that there be erected … and established ... an Academy or School for the education of youth in useful arts, sciences and literature, the … name and title of which shall be “The Pittsburgh Academy.”

Thus was chartered Pitt’s progenitor log house academy, a private school of higher learning and—in the words of founder Brackenridge—“a candle lit in the forested wilderness.” With a curriculum that included “the Learned Languages, English, and Mathematicks,” and, later, astronomy, philosophy, and logic, the Academy became one of the first institutions of advanced learning west of the Allegheny Mountains.

In the 1790s, the Academy trustees used a $5,000 legislative grant to construct a two-story, three-room brick schoolhouse on a corner lot in what now is the heart of downtown Pittsburgh. It—and a second building, adjoining the first and erected in the early 19th century—replaced the original log house, according to Pitt historian Robert C. Alberts, who penned Pitt’s bicentennial commemoration volume, Pitt: The Story of the University of Pittsburgh 1787–1987 (University of Pittsburgh Press, 1986).

From Academy to University

In much the same way that a budding nation required a new form of government that would be more responsive to its emerging needs, so, too, did the community of Pittsburgh—whose population had multiplied six times between 1794 and 1820—eventually require an academic institution with full university powers to better accommodate the region’s rising generations. Pitt historian Agnes Lynch Starrett, in her volume Through One Hundred and Fifty Years – The University of Pittsburgh (1937), reported that by 1819, “boys who became the leading men of Pittsburgh had been graduating from the Pittsburgh Academy for nearly thirty-five years” and, yet, they had to travel hundreds of miles to the east to enroll in a university.

That changed on Feb. 18, 1819, when the Pennsylvania legislature, upon the request of the Academy trustees, rechartered the school as the Western University of Pennsylvania. Its first principal, the Scottish-born Reverend Robert Bruce, supervised enlargement of the curriculum and, with a five-year legislative grant of $2,400 per annum, oversaw construction of a three-story freestone-fronted college building adjacent to the Academy on Third Street and Cherry Way. It became the University’s new home in 1830.

Fifteen years later, Pittsburgh’s Great Fire of 1845 destroyed several frame houses, along with the University’s records, books, and building. Classes met in the basement of the nearby Trinity Church during construction of a new site on downtown’s Duquesne Way. But in 1849, calamity struck a second time when fire destroyed that structure and its contents. Disheartened, the trustees temporarily suspended University operations until 1855, when the Western University reopened in a 16-room new brick building at the corner of Ross Street and Diamond (later renamed Forbes Avenue) in the city’s center.

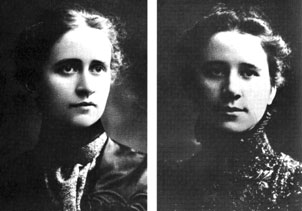

Sisters Margaret and Stella Stein were the first women to receive undergraduate degrees from the University in 1898.

Sisters Margaret and Stella Stein were the first women to receive undergraduate degrees from the University in 1898. An 1882 fire destroyed the Allegheny County Court House, and Western University sold its Ross and Diamond property to the county and relocated across the river to Allegheny City (today’s North Side), where it remained for more than 25 years. During that time, the University achieved racial integration—William Hunter Dammond earned a degree in civil engineering, with honors, in 1893 and became the University’s first African American graduate—and became coeducational, graduating its first female students—sisters Margaret and Stella Stein—in 1898 and its first Black female student, Jean Hamilton Walls, in 1910.

Building a Permanent Home

The first building of the Western University of Pennsylvania is shown here in a painting by Russell Smith. Courtesy of Carnegie Library of Pittsburgh.

The first building of the Western University of Pennsylvania is shown here in a painting by Russell Smith. Courtesy of Carnegie Library of Pittsburgh.When the cornerstone for the first building on the school’s new Oakland campus was laid in October 1908—to accommodate what was envisioned to become one of the finest institutions in the land—the Western University of Pennsylvania publicly was renamed the University of Pittsburgh.

The two-and-a-quarter-century journey that Pitt has traveled, from a private three-room frontier log academy to a nationally ranked, world-renowned public research university with a tripartite mission—leader in education, pioneer in research, and partner in regional development—includes milestones at virtually every turn. Among them are the following:

• Pitt’s School of Medicine—founded as the Western Pennsylvania Medical College in 1886—opened admission to women 100 years ago, in 1912.

• The University of Pittsburgh at Johnstown, one of the first regional campuses of a major U.S. university, was established 85 years ago, in 1927. A half-century ago, Pitt trustees approved the creation of regional campuses in Bradford, Greensburg, and Titusville.

• A gold medal, which has been on display in the Hillman Library, awaited Pitt freshman John Woodruff as he sprinted from behind and passed the pack of elite runners determined to cross the finish line in the 800-meter race at the 1936 Olympic Games in Berlin. Woodruff, who became Pitt’s first-ever gold medalist and the first Olympic medalist from Western Pennsylvania, earned his Pitt Bachelor of Arts degree in sociology in 1939. He died in October 2007, at age 92.

• The cornerstone of the 42-story Cathedral of Learning was laid in the Commons Room 75 years ago, on

June 4, 1937, along with a statement that reads, “The Cathedral of Learning expresses for Pittsburgh a desire to live honestly in a world where kindness and the happiness of creating are life.”

Also in 1937, U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt announced the establishment of the National Foundation for Infantile Paralysis (NFIP), which later became known as the March of Dimes, to help conquer polio—a deadly and crippling infectious disease whose victims all-to-frequently were confined to mechanical ventilators (“iron lungs”) or wheelchairs, and/or had to use crutches and wear braces. The worst polio epidemic in our nation’s history occurred during the summer of 1952, with 57,628 cases. The following May, Pittsburgh became the site of the first community-based pilot trial of the polio vaccine developed at Pitt with NFIP funding by a team of Pitt researchers led by Jonas Salk with now Pitt Distinguished Service Professor Emeritus Julius Youngner as senior scientist. Less than two years later—on April 12, 1955—the country breathed a collective sigh of relief as the polio vaccine publicly was declared “safe, effective, and potent.”

The Pitt research team’s Jonas Salk (left) and Julius Youngner at work on the vaccine developed at Pitt in the 1950s.

The Pitt research team’s Jonas Salk (left) and Julius Youngner at work on the vaccine developed at Pitt in the 1950s. In 2005, during Pitt’s 50th anniversary celebration of the confirmation of the Salk vaccine’s efficacy, Pitt Chancellor Mark A. Nordenberg invoked the Journal of the American Medical Association, which heralded the development of the polio vaccine as “one of the greatest achievements of the 20th century.”

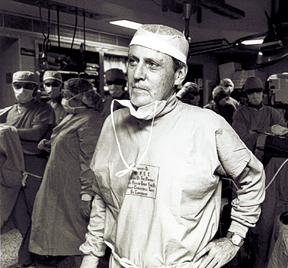

Imagination, hard work, and ingenuity sparked the Pitt research team’s development of the polio vaccine. These qualities continue to inspire Pitt faculty, staff, and students and contribute to Pitt’s reputation as a pioneer in research. One telling example is Distinguished Service Professor Thomas E. Starzl—known to most as the “Father of Transplantation”—who performed the world’s first human liver transplant and the world’s first double transplant, the latter in Pittsburgh in 1984. Twenty years later, in 2004, Starzl was awarded the National Medal of Science, this country’s highest scientific honor, “for his pioneering work in liver transplantation and his discoveries in immunosuppressive medication that advanced the

Organ-transplantation pioneer and recipient of the National Medal of Science Thomas E. Starzl

Organ-transplantation pioneer and recipient of the National Medal of Science Thomas E. Starzlfield of organ transplantation.” Starzl received the presidential honor at a White House ceremony in 2006. Closer to home, Pitt’s Transplantation Institute, the University’s original biomedical science tower, and an Oakland Street all have been named after Starzl.

Joining the cast of Pitt luminaries are faculty, students, and alumni who are leading the way in areas as diverse as biotechnology, engineering, computer modeling, creative writing, the performing and visual arts, education, gerontology, regenerative medicine, health sciences, government, law, nanotechnology, business, international studies, social innovation, philosophy of science, urban education, sustainability, sports, and public service, among many other areas.

State-Related University

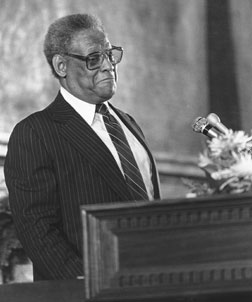

One of the most important and influential public servants in Pennsylvania’s rich history, in fact, was K. Leroy Irvis,

The Honorable K. Leroy Irvis

The Honorable K. Leroy Irvisa 1954 alumnus of the University of Pittsburgh School of Law, and a longtime Pitt trustee, who, as Pennsylvania’s first African American speaker of the House, was the nation’s first Black speaker of any state House of Representatives since Reconstruction. Irvis sponsored more than 1,600 pieces of legislation throughout his more than 30 years in public life. Chief among them was the bill, enacted in 1966, that made Pitt a state-related university and saved it from financial disaster.

According to Pitt historian Robert Alberts, this so-called “joint venture in public-private support for higher education” relieved the Commonwealth of the huge capital investment that would have been required to build a state university that would educate Pennsylvania’s students. The partnership, which dramatically increased the University’s support from Commonwealth funds, also enabled Pitt to lower its tuition for Pennsylvania residents, causing a surge in freshman applications.

Among the students attracted to Pitt was the legendary Tony Dorsett, a native of Aliquippa and one of the greatest running backs in college and pro football history. Starring at Pitt from 1973 to 1976, Dorsett led the Panthers to the 1976 national championship with a season record of 12-0. That triumph earned the Panthers the designation, “one of the greatest teams of all time,” and Dorsett’s stellar performance made him the runaway choice for the 1976 Heisman Trophy.

The following year, 1977, marked the arrival at Pitt of someone who would become another Pitt champion—Mark A. Nordenberg, who was preparing to begin a nine-month stint as a visiting assistant professor at the University of Pittsburgh School of Law. Some 35 years later, he remains at Pitt; and for nearly 17 of the past 25 years, he has served as the University’s chancellor.

“One of the finest and most productive universities in the world”

During Mark Nordenberg’s first year of service, as interim chancellor, the Board of Trustees commissioned an external review of Pitt that highlighted problems such as falling enrollment, low morale, and inefficient business practices. In response, the Board in early 1996 adopted five priority statements that committed Pitt to aggressively pursue excellence in undergraduate education, maintain excellence in research, partner in community development, ensure operational efficiency and effectiveness, and secure an adequate resource base. By 2000, with Pitt already having achieved some measure of success, the Board more generally declared that “[b]y aggressively supporting the advancement of Pitt’s academic mission, we will clearly establish that this is one of the finest and most productive universities in the world.”

Holding fast to those broad and enduring statements of aspiration has yielded striking and measureable results, among them:

• Pitt enrolled its strongest freshman class from its largest applicant pool ever at the beginning of this academic year, and the level of student talent continues to soar. This past December, for example, Cory J. Rodgers became the seventh winner of the prestigious Rhodes Scholarship to have received a Pitt undergraduate education, and the fourth in the past seven years. That victory made Pitt one of only two public institutions in the United States to have claimed the award at least four times in the last seven years.

• Pitt’s robust record of educating outstanding students who earn the highest forms of national and international recognition also includes since 1995 six Marshall Scholarships, five Truman Scholarships, five Udall Scholarships, one Gates Cambridge Scholarship, one Churchill Scholarship, and 35 Goldwater Scholarships.

• Pitt’s high-achieving faculty regularly have won exceptional honors—including, in recent years, the National Medal of Science; the Charles S. Mott Prize, widely regarded as the highest honor in cancer research; and the MacArthur “Genius” Award, for extraordinary originality and dedication in creative pursuits and a marked capacity for self-direction. Faculty also have been elected to membership in esteemed groups, among them the National Academy of Sciences, the Institute of Medicine, and the American Association for the Advancement of Science.

• Pitt’s annual research expenditures last year topped a record-setting $800 million, a well-acknowledged sign of institutional strength. In fact, Pitt ranks fifth among all U.S. universities in terms of the competitive grants awarded to its faculty by the National Institutes of Health and ranks in the top 10 nationally in total federal science and engineering research and development support.

• Pitt was the nation’s top-ranked public “Best Neighbor” university in the 2009 edition of Saviors of Our Cities: A Survey of Best College and University Civic Partnerships. Best neighbor universities are distinguished by their longstanding efforts with community leaders to rehabilitate the cities around them, to influence community revitalization and cultural renewal, and to encourage economic expansion, urban development, and community service.

• Pitt’s Building Our Future Together capital campaign—already the largest and most successful fundraising campaign in the history of Western Pennsylvania—has exceeded $1.9 billion in gifts and pledges and is well within range of its landmark $2 billion goal. The impact of that giving includes ever-growing levels of endowed scholarship, fellowship, and faculty support as well as other key investments in Pitt’s people, programs, and facilities.

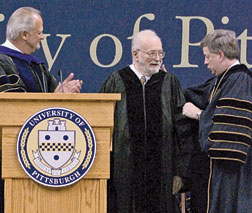

2003 Nobel Laureate in Medicine recipient Paul Lauterbur with Chancellor Nordenberg

2003 Nobel Laureate in Medicine recipient Paul Lauterbur with Chancellor Nordenberg 2004 Nobel Peace Prize recipient Wangari Muta Maathai

2004 Nobel Peace Prize recipient Wangari Muta MaathaiAny university makes many of its most important contributions through the work of its graduates, and Pitt alumni are no exception. Some of their work, which has extended well beyond Pitt’s campuses, has contributed to the greater good and improved the human condition. Think of Pitt graduate Paul Lauterbur, who was named a 2003 Nobel Laureate in Medicine for his groundbreaking work in the science of magnetic resonance imaging, or of Pitt graduate Wangari Muta Maathai, who a year later received the 2004 Nobel Peace Prize for her contributions to sustainable development, democracy, women’s rights, and peace.

Among the many other important forms of recognition that Pitt graduates have won for the quality and impact of their lives’ work are the National Medal of Science, the Shaw and Albany Prizes in medicine, the Fritz Medal in engineering, the Templeton Prize, the Pulitzer Prize for fiction, the National Book Award for Poetry, the Grammy award, the Goi Peace Prize, the MacArthur Fellowship, and the Grainger Challenge Prize for sustainability.

“Leader in education. Pioneer in research. Partner in regional development.” The tripartite mission of the 21st-century center of higher learning known as the University of Pittsburgh bears repeating—and particularly now, as Pitt, which already has touched four centuries, celebrates its 225th birthday by further extending its long and proud history of building better lives.

Other Stories From This Issue

On the Freedom Road

Follow a group of Pitt students on the Returning to the Roots of Civil Rights bus tour, a nine-day, 2,300-mile journey crisscrossing five states.

Day 1: The Awakening

Day 2: Deep Impressions

Day 3: Music, Montgomery, and More

Day 4: Looking Back, Looking Forward

Day 5: Learning to Remember

Day 6: The Mountaintop

Day 7: Slavery and Beyond

Day 8: Lessons to Bring Home

Day 9: Final Lessons