Pitt’s Delanie Jenkins Draws From the Physical, Emotional Realms to Engage Audiences

Entering Delanie Jenkins’ art studio is a bit like stepping through Alice’s Looking Glass. As enchanting as fairy dust … as curious as a Greenwich Village boutique … the tiny room is crammed with bizarre treasures and collections.

Entering Delanie Jenkins’ art studio is a bit like stepping through Alice’s Looking Glass. As enchanting as fairy dust … as curious as a Greenwich Village boutique … the tiny room is crammed with bizarre treasures and collections.

From pumpkin stems to radish roots … avocado skins to rose petals … this is the stuff of which Jenkins’ art is made.

“There may be a day three years from now where I’ll have an ‘Aha!’ moment about something I’ve been collecting for 15 years,” said Jenkins, surrounded by shelves of glass bins filled with everything from used tea bags to clam shells. “Even if there is no moment like that, there is still something intrinsically interesting about these things, enough so that I am still compelled to collect it.”

The Dallas native came to Pitt in 1996 when she accepted a post on the University’s Studio Arts faculty. She is now chair of the department.

And while Jenkins’ pace is generally frenetic, it became more so last year when the Pittsburgh Center for the Arts named her its 2007 Artist of the Year. Jenkins filled seven of the center’s galleries with her newest work. It marked the first time in the Artist of the Year exhibition’s 58-year history that performance art was featured. Performance art refers to exhibitions where the artist is engaged in some type of activity as an integral part of the presentation.

Among the works displayed by Jenkins was “11,280 Strands and Counting…,” which featured 10-foot-tall digital prints of Jenkins’ own thick auburn hair. Her hair stylist had handed her three fat ponytails following a haircut. And although Jenkins swore she would not make art from them, she reconsidered.

“I was surprised by the weight of them,” she recalled. “I felt like I was holding an organ from my body.” She began wondering how many strands there were and, inspired by the cliché—“How far could she go on her beauty?”—she began to calculate the literal distance. Visitors to the exhibition found Jenkins seated at a table, measuring and counting. To date, she’s counted more than 14,000 strands, totaling more than two miles.

“Traces of Absorption” paid homage to the quilted texture patterns of paper towels. It included a series of white-on-white etchings, a video installation, and eight “towels” cast in white chocolate, two on a shelf leaning against the gallery wall and the remaining six in a glass case.

“I wanted to make an impact less directly, not so in-your-face,” she explained. “Because the works are so subtle, the viewer had to be interested enough to move closer, to discover the work.” Some art viewers smelled the chocolate as soon as they walked in to the room, but couldn’t figure out its location.

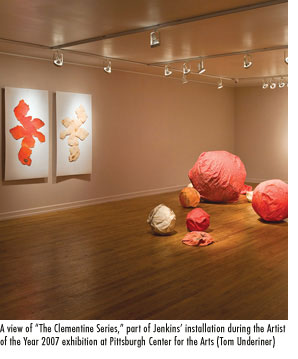

Less subtle was “The Clementine Series,” huge ink-jet prints of the interior and exterior skins of peeled Clementines. Jenkins enlarged one print of the inside of a peel to eleven feet and placed it on the floor with low lights hovering above. Others were reincarnated as etchings. And some of the prints were enlarged, cut out, and reassembled with stitching into giant soft sculptures.

Less subtle was “The Clementine Series,” huge ink-jet prints of the interior and exterior skins of peeled Clementines. Jenkins enlarged one print of the inside of a peel to eleven feet and placed it on the floor with low lights hovering above. Others were reincarnated as etchings. And some of the prints were enlarged, cut out, and reassembled with stitching into giant soft sculptures.

That idea stemmed from a solemn antiwar protest that Jenkins and her young daughter, Lila, had taken part in on a dark grey winter day. When Jenkins pulled a bright orange Clementine from her pocket, she said “the contrast of color and form of that object in that dark and foreboding environment seemed somehow hopeful and emblematic of my world at that moment—and because of that, worth exploring.”

“That work came from such a serious place,” she said. “It’s really about death and decay. So I was surprised at how fun, and even awkwardly funny, that body of work became.”

Jenkins’ art comes from a very personal place—motherhood, childhood memories, and the like. Process is crucial to her explorations, as is a physical engagement for the viewer.

For example, thousands of Pittsburghers saw Jenkins’ work on a routine basis in 2003, when she created a live Honeysuckle Room in Frank Curto Park alongside busy Bigelow Boulevard. It was part of the Persephone Project’s Art Gardens of Pittsburgh.

The “room,” one component of the garden, had windows in it—one for adults and one for children. Participants could walk in and look out at a view of the Allegheny River and the Northside. Jenkins also planted loofah sponge and cotton plants to harvest for another body of work. She said that in June, when the honeysuckle was blooming, the room and the scented herb bed below the windows could be “intoxicating.” Motorists would get off at the access road and stop to have lunch there or chat with Jenkins as she tended the garden. She recalled with a smile a visit she had with two Egyptian men who stopped by out of curiosity.

“Egyptian cotton is some of the finest cotton. These men knew all about the history of cotton in their country, but had never seen an actual cotton plant!” she said.

Jenkins credits her interest in installation art to her background in designing amusement parks and entertainment facilities as a young woman in Dallas. The design team would come up with a layout that took people from the roller-coaster to the corn dogs, then to a live show, then the funnel cakes—moving the crowd at a leisurely pace that allows them to spend the most money. After five years and realizing that she was “controlling the landscape for the sake of commerce,” she returned to art school.

Now with her installations, no money changes hands, but people are still enticed to slow down and take it all in.

“With installation, as soon as you cross that threshold into a space, you are physically engaged and responding on a number of levels. You can be uncomfortable. You can luxuriate. You can say ‘I hate this and I’m leaving.’ But you’re still having a complex response physically, perhaps emotionally, psychologically, and intellectually,” she said.

Jenkins is digging into her role as department head, helping to guide 130 studio arts majors and 11 faculty members whom she calls “amazing artists.” Pitt’s studio arts majors are submitting to exhibitions and film festivals, getting their work shown, and winning awards.

She and her husband, who teaches at the Art Institute of Pittsburgh, and Lila, reside in Point Breeze. They enjoy Pittsburgh, although—coming from Dallas and Boulder, Colo.—the grey overcast days of winter still take some getting used to. That explains the small blue spectrum lamp on Jenkins’ desk in her basement studio/office.

And Jenkins herself is a student, a devotee of yoga for the past 13 years.

“It’s really helped me be a better teacher and have great compassion for my students,” she said. “It’s good to be humbled every day.”

Other Stories From This Issue

On the Freedom Road

Follow a group of Pitt students on the Returning to the Roots of Civil Rights bus tour, a nine-day, 2,300-mile journey crisscrossing five states.

Day 1: The Awakening

Day 2: Deep Impressions

Day 3: Music, Montgomery, and More

Day 4: Looking Back, Looking Forward

Day 5: Learning to Remember

Day 6: The Mountaintop

Day 7: Slavery and Beyond

Day 8: Lessons to Bring Home

Day 9: Final Lessons