Researchers Aim to Change Tissue Microenvironment to Fight Cancerous Tumors

In an effort to attack cancerous tumors more effectively, researchers at the University of Pittsburgh Cancer Institute are working with substances to alter the immunological microenvironment around the tumor instead of developing new drugs that directly target the tumor.

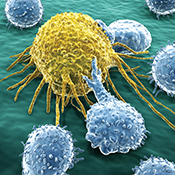

Specifically, researchers are trying to manipulate the tumor microenvironment—or the cells, molecules, and blood vessels that surround and feed a tumor cell—to promote the infiltration of the human body’s immune killer cells called cytotoxic T cells. Multiple studies worldwide have demonstrated that the infiltration of tumor tissues with these killer cells improves the prognosis of cancer patients.

to manipulate the tumor microenvironment—or the cells, molecules, and blood vessels that surround and feed a tumor cell—to promote the infiltration of the human body’s immune killer cells called cytotoxic T cells. Multiple studies worldwide have demonstrated that the infiltration of tumor tissues with these killer cells improves the prognosis of cancer patients.

During a recent presentation at the Cancer Vaccines and Gene Therapy Meeting in Malvern, Pa., Pawel Kalinski, a professor of surgery in the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine, presented laboratory data in support of using “combinatorial adjuvants”—or pharmacological agents that are added to a drug to increase or aid its effect. These adjuvants induce desirable patterns of tumor-associated inflammation, resulting in the infiltration of cytotoxic T cells into tumors.

Kalinski also discussed preliminary data from a phase I/II trial led by Amer Zureikat, an assistant professor of surgery in the Pitt School of Medicine, in which colorectal cancer patients were given escalating doses of interferon alpha in combination with a COX2 blocker and Ampligen®.

“The first part of the trial is not complete, but so far it appears that the treatment was well-tolerated,” Kalinski said. “Our early observations are completely consistent with our preclinical predictions: they hint that the combination therapy may be altering the tumor environment to make it more susceptible to immune attack. We are hopeful that the next, randomized part of the study will directly demonstrate the difference between the tumors of patients receiving standard treatment of chemotherapy and surgery—and the patients receiving additional immunotherapy, which would lead us to expect a therapeutic benefit to this strategy.”

is not complete, but so far it appears that the treatment was well-tolerated,” Kalinski said. “Our early observations are completely consistent with our preclinical predictions: they hint that the combination therapy may be altering the tumor environment to make it more susceptible to immune attack. We are hopeful that the next, randomized part of the study will directly demonstrate the difference between the tumors of patients receiving standard treatment of chemotherapy and surgery—and the patients receiving additional immunotherapy, which would lead us to expect a therapeutic benefit to this strategy.”

Tumors are typically able to undermine the body’s immune defenses, sending out cellular signals that call in regulatory T-cells to suppress the activity of natural killer cells, he explained. While there are many adjuvants available to enhance immune system response, most are nonselective, meaning they do not produce immune responses that specifically target the tumor, and therefore are ineffective.

In the second part of the study, which could begin early next year, colorectal cancer patients will be randomly assigned to receive either conventional treatment with chemotherapy followed by surgical removal of the tumor, or additionally to receive two cycles of the interferon alpha-based chemokine-modulatory regimen between chemo and surgery.

“After surgery, we will be able to compare the tumors from the two groups to see if there is a difference in their immunological microenvironment that could be beneficial,” Kalinski said. “This adjuvant strategy might also work for many other kinds of cancers because it’s not targeting specific tumor markers, but boosting the immune system’s own ability to find cancer cells and destroy them.”

He added that future efforts would aim to add a vaccine component based on dendritic cells, which recognize foreign proteins to stimulate an immune response against them. That strategy, too, would rely on boosting the body’s own defenses rather than providing a specific tumor marker as a target.

Other Stories From This Issue

On the Freedom Road

Follow a group of Pitt students on the Returning to the Roots of Civil Rights bus tour, a nine-day, 2,300-mile journey crisscrossing five states.

Day 1: The Awakening

Day 2: Deep Impressions

Day 3: Music, Montgomery, and More

Day 4: Looking Back, Looking Forward

Day 5: Learning to Remember

Day 6: The Mountaintop

Day 7: Slavery and Beyond

Day 8: Lessons to Bring Home

Day 9: Final Lessons