UAG Exhibition Reveals Beauty, Artists’ Introspection During a Journey Amid Dinosaur Bones

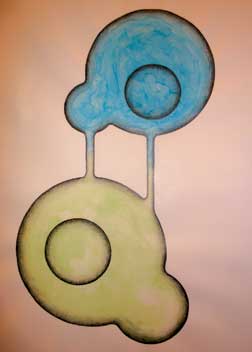

'Together (Symbiosis)' by Rob Hackett

'Together (Symbiosis)' by Rob HackettOn a Wyoming ranch rich with dinosaur bones and never-ending vistas, four Pitt University Honors College students worked day and night on their art. Armed with the usual artistic tools—paint and paintbrushes, canvases, cameras—the young artists also relied on their strong arms to carry objects to create sculptures and their observant eyes to assess the new territory.

The students were participants in Pitt’s second annual Wyoming Field Study, a 16-day, three-credit course offered in conjunction with the University Honors College. Their charge: to study and create art at Cook Ranch, the 4,700-acre parcel of land on the High Plains of Wyoming that was donated to Pitt five years ago. Accompanying them was Pitt art professor Delanie Jenkins, chair of the Department of Studio Arts.

Their time on the ranch produced a panoply of colorful and, at times, introspective paintings, drawings, and sculptures. Interestingly, not a dinosaur bone is to be found in any of them. Sixteen works from their summer 2010 adventure are on display in the Studio Arts Wyoming Field Study Exhibition, which runs through Jan. 28 in the Frick Fine Arts Building’s University Art Gallery. All four students will be in the gallery at noon Jan. 26 to discuss their work.

Jenkins and the students drove across the country last June to Cook Ranch. They set up their studio in a nearby 1919-era bank building in Rock River; they roomed at a hotel with other Honors College students who were enrolled in an on-site paleontology course. The overlapping courses are part of the University’s commitment to use the land for multidisciplinary education and research.

“It was fun to interact with the science students,” said Ellyn Womelsdorf (A&S ’10), who studied in Wyoming as a postbaccalaureate art student. “They learned from us, and we learned from them,” she added, saying that the science students would pop into the studio to see the artists’ work, and vice versa.

The Cook Ranch was rich with inspiration, the young artists said. Rob Hackett, who will graduate this December, hiked to the top of Medicine Bow Peak and took seven photographs of the sweeping vistas. He then “stitched” them together to create a wide panorama that is part of the exhibition.

Womelsdorf, meanwhile, found inspiration in a tiny mosquito, from the swarms that would cling to the studio’s screen door at night. She drew one mosquito against a red backdrop created from a mixture of waterproof and acrylic ink. She poured the ink onto the paper, then dripped denatured alcohol on the surface, creating a kind of mottled tie-dyed effect. Similarly, additional pieces with blue, green, or yellow backgrounds feature other Western iconography—a snow fence, windmills, and a pronghorn antelope.

Nickolas Reynolds, who will graduate in April, said he had decided beforehand that he would create watercolors of landscapes. But on the way to the site, he kept noticing abandoned cars with grasslands sprouting from where the seats had once been. “People had deserted these cars with the intention of coming back,” he said, adding that some Rock River residents abandon houses in the same fashion.

'Untitled' by Nickolas Reynolds

'Untitled' by Nickolas ReynoldsReynolds’ explorations took him to the local dump, which was heaped with piles of rusted junk. One of his exhibition pieces is a mobile made of hubcaps, a rusted license plate, and large railroad spikes. When touched, the rusty pieces of metal clink against one another and evoke a surprisingly delicate tinkling sound, like glass chimes.

The fourth student, Ben Danforth, created what he calls a “highly symbolic” body of work using ink and gouache on paper. What surprised him the most was how well he functioned with no distractions.

“Students in a BA program rarely have time to think solely about artwork and reflect on its development,” said Danforth, who graduated last month from the School of Arts & Sciences. “Having nothing to focus on but one’s work was an enormously beneficial experience.”

Danforth says he was inspired by the grand scale of things, and that the enormous Wyoming sky helped him put in perspective his own existence in the world.

“It was amazing to watch the students struggle with their sense of time, place, and landscape in relation to their own work,” said Jenkins, who managed to carve out a side trip to Denver, where the students visited galleries, an art museum, and two of her artist friends who work out of studios in the Colorado mountains.

On the ranch, the students hiked together and individually. They crawled over boulders, explored an alley where a nighthawk had taken up residence in an abandoned house, and watched a golden eagle soar into flight right in front of them. Each student kept a journal; in fact, every word of Womelsdorf’s journal was recopied to form the backdrop for one of her large pieces in the exhibition.

Jenkins called the Studio Arts Wyoming Field Study a “microcosm of graduate school,” not unlike a Master of Fine Arts program. “It was a dedicated round-the-clock studio space with a community of peers engaged in similar work,” she said. “The students had a sense of purpose rooted in curiosity, experimentation, and creative problem solving.”

Most of the art and paleontology students have kept in touch with one another since last year’s adventure.

“My roommate out in Wyoming is now my roommate here in Pittsburgh,” smiled Womelsdorf.

Other Stories From This Issue

On the Freedom Road

Follow a group of Pitt students on the Returning to the Roots of Civil Rights bus tour, a nine-day, 2,300-mile journey crisscrossing five states.

Day 1: The Awakening

Day 2: Deep Impressions

Day 3: Music, Montgomery, and More

Day 4: Looking Back, Looking Forward

Day 5: Learning to Remember

Day 6: The Mountaintop

Day 7: Slavery and Beyond

Day 8: Lessons to Bring Home

Day 9: Final Lessons